NOTE: This past February 3 was the 63rd anniversary of the plane crash in northern Iowa which took the lives of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, J.P. Richardson aka The Big Bopper, and pilot Roger Peterson. Most of the information in today’s post was originally written by me and posted on the Philco Phorum on August 31, 2019.

As regular readers of this blog already know, I was diagnosed with stage 4 colorectal cancer with metastis to my lungs in August 2018. After having undergone a couple rounds of chemotherapy, we decided to take what I thought at the time might be my last long trip. We would go to Addison, Illinois, where the Antique Radio Club of Illinois would be hosting the great Radiofest swap meet. From there, we would drive on to Clear Lake, Iowa.

Why Clear Lake?

If you know your rock and roll history, you know that Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper (J.P. Richardson) were killed in a plane crash in the very early morning of February 3, 1959, near Clear Lake. They had just performed at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake the evening of February 2.

Now, I would like to fill you in on the backstory of what has become known as “The Day the Music Died.”

This oversize pair of glasses marks the beginning of the trail leading to the plane crash site just north of Clear Lake, Iowa.

Winter Dance Party 1959 Tour

Many people tend to forget that the tour not only featured Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. Richardson (aka The Big Bopper), but also Dion and the Belmonts, and opening act Frankie Sardo. For the tour, Buddy used a new group of “Crickets” he had put together after original Crickets Jerry Allison and Joe B. Mauldin quit – Waylon Jennings (yes, the same Waylon Jennings who would go on to a career in country music, best known as one of the “Outlaws” with Willie Nelson and others) on electric bass, Tommy Allsup on rhythm guitar, Carl Bunch on drums. Thom Mason, a saxophone player, was hired to play in the band as well as a trumpet player (I don’t have his name at present). This band played behind all of the performers (Frankie Sardo, Dion & The Belmonts, the Big Bopper, Ritchie Valens, as well as Buddy Holly) at each concert, so they had to work hard!

Frankie Sardo was added to the tour as the opening act based on a minor hit he had had called “Fake Out”. On most of the posters advertising the tour, Frankie’s song is erroneously listed as “Take Out”.

The tour began on January 23, 1959, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The guys had to play every night in a different town. Every night. To make matters worse, the promoters had booked the concerts in a haphazard fashion, so that they were crisscrossing the northern Midwest in a zigzag pattern, traveling hundreds of miles from town to town. And to top it all off, the heater in their bus did not work very well, if at all. This was with outside temperatures in double digits below zero.

Your author posing behind the oversize glasses. Photo by Debbie Ramirez

The Belmonts

Carlo Mastrangelo, Fred Milano, and Angelo D’Aleo were friends who grew up in the same part of the Bronx, New York. They began singing together as teenagers. They named themselves “The Belmonts” after the name of the street Milano lived on – Belmont Avenue. After making a record in 1957 that went nowhere, Dion DiMucci (a fellow Italian American from the Bronx) recruited them to join him in a musical act. Dion and the Belmonts would have an all too brief period (1958-1960) of great success before Dion left the Belmonts to go solo.

But I’m getting ahead of myself a little bit. In 1958 Angelo D’Aleo, the Belmonts’ high tenor singer, was drafted into the Navy. So, on the Winter Dance Party tour, Dion and the Belmonts were a trio – Dion DiMucci, Carlo Mastrangelo, and Freddie Milano.

Trouble

The constant subzero temperatures and little to no heat on the bus ultimately caused drummer Carl Bunch to get frostbite in his feet after the bus broke down on the road on February 1. He was hospitalized and had to leave the tour. Carlo Mastrangelo was an accomplished drummer as well as a singer, so he sat in on drums in Bunch’s absence. When it was Dion and the Belmonts’ turn to perform, either Ritchie Valens or Buddy Holly sat in on drums. A picture of Dion and the Belmonts performing at the Surf Ballroom appears to show Buddy Holly on drums.

The crash site in a field near Clear Lake. The stainless steel monument to Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and J.P. Richardson is placed at the spot where the plane came to a stop. The monument to pilot Roger Peterson was added later.

The Ill-Fated Plane

Buddy Holly had had enough of the severe cold and the long bus trips. Tommy Allsup said, many years later, that Buddy tried to charter a plane in Green Bay on February 1, apparently without success. During an intermission at the Surf concert the evening of February 2, Buddy asked Carroll Anderson, who was manager of the Surf Ballroom at the time, to contact Dwyer’s Flying Service in nearby Mason City, Iowa. Anderson was able to charter a plane on Buddy’s behalf. The original intention was that Buddy, Waylon Jennings, and Tommy Allsup would fly on to Fargo, ND – just across from Moorhead, MN, site of their next concert – and catch up on sleep, laundry, etc.

J.P. Richardson (The Big Bopper) was sick and asked Waylon Jennings if he could take Waylon’s seat on the plane and Waylon agreed. When Ritchie Valens found out, he repeatedly asked Tommy Allsup if he could take Tommy’s place on the plane. Tommy initially refused, but eventually, Tommy agreed to a coin flip between himself and Ritchie for the plane seat. Ritchie won the flip and took Tommy’s place on the plane.

In recent years, Dion has claimed that Buddy asked Ritchie, J.P., and himself to determine who would fly on the plane. He has told one story that there was a coin flip between himself and Ritchie and that he (allegedly) won the flip but let Ritchie go because Ritchie was sick. According to another story, Dion elected not to go because of the cost of the plane ride – the $36 fare was the same amount Dion’s parents paid for rent each month for their house and Dion considered the fare excessive.

These stories are in direct conflict with the Tommy Allsup – Ritchie Valens coin flip story. The Allsup – Valens coin flip story was corroborated by Waylon Jennings, Frankie Sardo, Carl Bunch, and then-KRIB (Mason City, Iowa) DJ Bob Hale, who was the master of ceremonies at the Surf Ballroom during the February 2 concert.

Even the Allsup – Valens coin flip story has two versions. Tommy Allsup stated that he flipped the coin, while Bob Hale’s version of the story goes that Tommy discovered he had no coins as soon as he suggested a coin flip, so Hale flipped a coin. Hale later said that he and Allsup had discussed the flip years later and agreed that regardless which version is correct, that night was certainly a tragic one. [1]

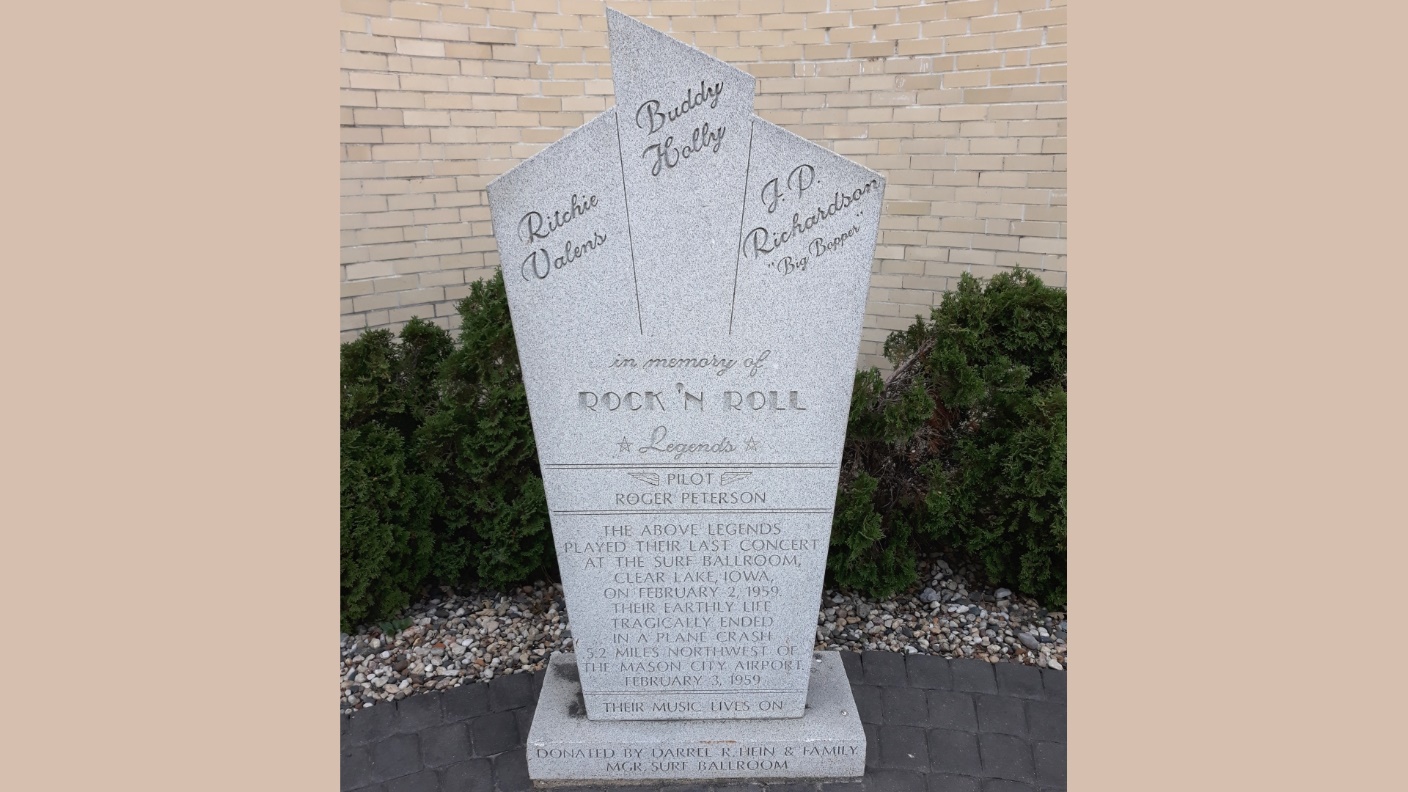

This monument stands just to the right of the entrance of the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake.

Once Buddy Holly learned that Waylon Jennings had given up his seat on the plane to the Big Bopper, Buddy said to Waylon, jokingly: “Well, I hope you ol’ bus freezes up.”

Waylon’s reply, also in jest: “Well, I hope your ol’ plane crashes.”

Those words, meant only as a joke between friends, would haunt Waylon Jennings for the rest of his life.

Roger Peterson, a young pilot who had recently failed his instrument test, agreed to fly the plane to Fargo.

Only Peterson, Holly, Valens and Richardson would know what happened on that fateful flight – and none of them lived to tell about it. All four were killed on impact when the plane went down in a cornfield a few miles north of Clear Lake.

Don McLean’s 1972 monster hit American Pie immortalized February 3, 1959 as “the day the music died”.

While the anniversary of February 3 is a sad time in rock and roll history, I am so glad I was able to make that trip to Clear Lake, especially now that I am no longer able to travel long distances as a result of the surgery I had to have to remove the main tumor. Being able to visit the Surf Ballroom and the crash site just north of Clear Lake has left me with wonderful memories.

A footnote: Bob Hale, who was a DJ at station KRIB in Mason City at the time of the February 2, 1959 concert at the Surf Ballroom, would eventually move on to WLS in Chicago to become one of their original “Swingin’ Seven” DJs when WLS changed formats from rural-oriented programming to rock and roll on May 2, 1960. Hale later went on to a career in television in Chicago and then Lexington, KY before returning to Chicago.

[1] https://chicagoradiospotlight.blogspot.com/2008/04/bob-hale.htmlFurther reading:

Flashback: February 3, 1959, The Day the Music Died in Iowa

Flashback: How Waylon Jennings Survived the Day the Music Died

How a coin toss cost this pioneering Hispanic musician his life on ‘The Day the Music Died’

The Winter Dance Party Tapes: Extended Trailer

This Day In History: The Day The Music Died

Tommy Allsup, Guitarist Who Avoided ‘Day The Music Died’ Crash, Dead at 85

Tommy Allsup tells of the coin flip with Ritchie Valens

Waylon Jennings’ Close Call on ‘The Day the Music Died’

Waylon Jennings Recalls Final Moments Before Buddy Holly’s Tragic Plane Crash

Who Flipped a Coin With Ritchie Valens?: The Day the Music Died and the Coin Toss Controversy

Buddy’s buddies fight over coin toss on fateful night (paywall)

Suburban man recalls ‘day the music died’ (paywall)

Photo at top: The Surf Ballroom, Clear Lake, Iowa. Photo by the author.